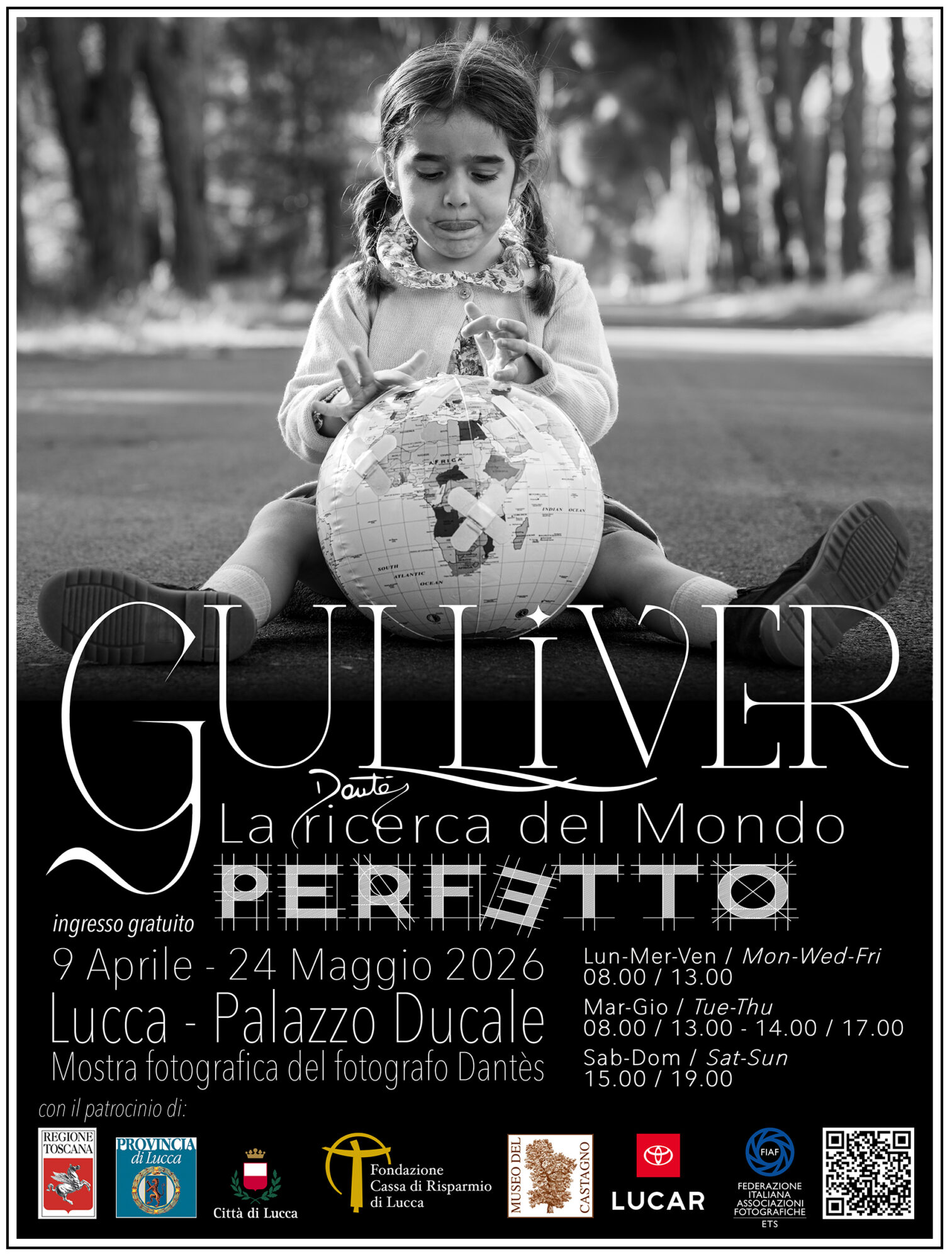

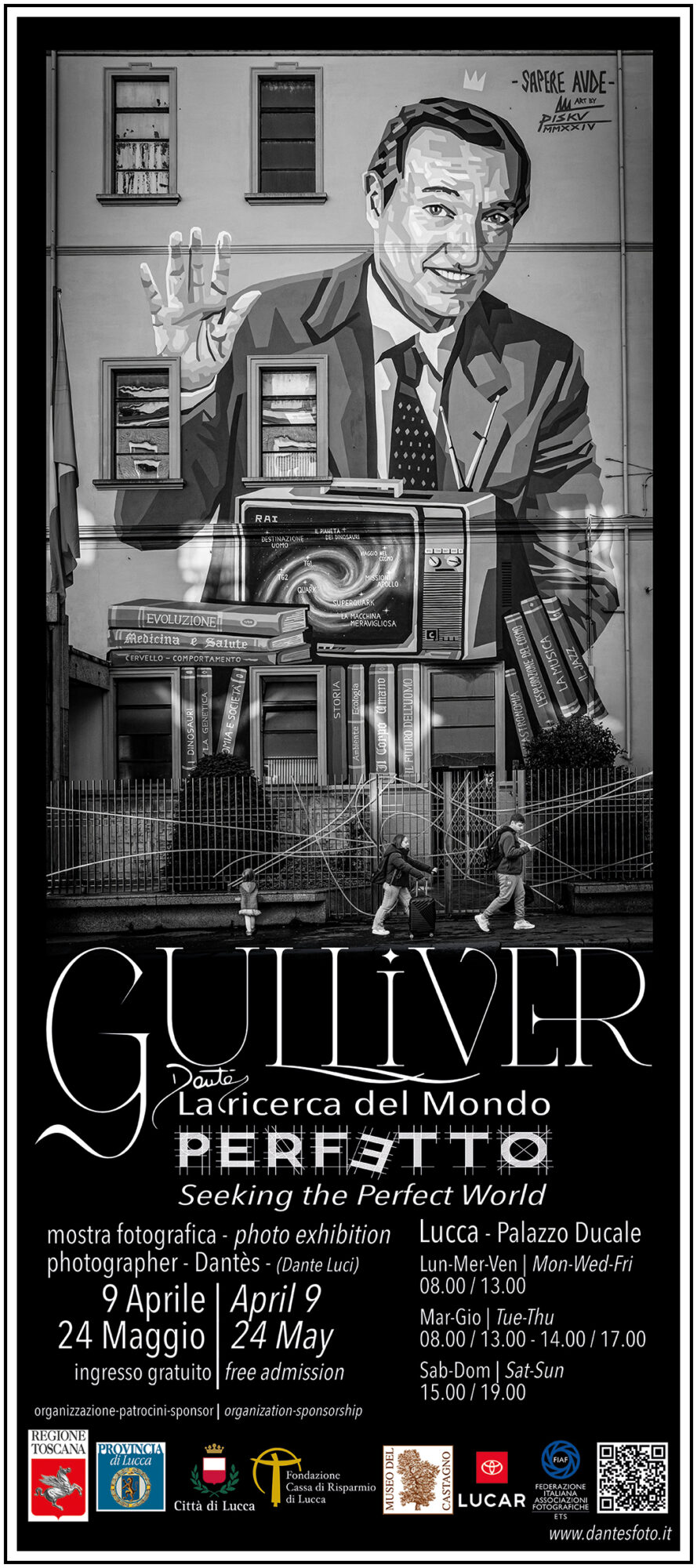

Seeking the Perf(e)ct World

The new reportage by photographer Dantès (Dante Luci) is on display at the Palazzo Ducale in Lucca. 7 weeks: From April 9th to May 24th, 2026

Gulliver: The Search for the Perfect World is a journey where images and text merge for an immersive narrative experience that uses the visual power of black-and-white photography to tell stories, explore places, social dynamics, and perhaps even express concepts. These are complemented by short texts such as captions, quotes, and introductory reflections to each chapter, creating a single, profound narrative.

With this photographic project, Dantés guides us along a complex and structured journey that focuses on fundamental themes such as school, inclusion, integration, acceptance, and legality. These are sensitive and important social issues that constitute the fundamental elements that underpin civil life and represent the building blocks for the future.

These powerful and gentle images, incisive and tender, encourage us to maintain a sense of belonging to the community, with a vision that is not superficially optimistic but rather seeks to capture the positive aspects of feelings and attitudes.

Dantés’s photographs have an inner strength and are destined to endure, to remain in our hearts. They constitute a powerful narrative and symbolic tool for recalling fundamental values, analyzing the current situation, and inspiring people and observers toward a future of cohesion and peace. These images transcend retinal vision to become the expression of a quest, a conceptual journey, transforming into an image-metaphor of suggestions, feelings, and concepts.

Why Gulliver?

The masterpiece “Gulliver’s Travels” by English writer Jonathan Swift is organized into four different parts. Each section, dedicated to a journey, describes a society inhabited by fantastical characters in which Gulliver tries in vain to adapt. The protagonist, like Dantès, is searching for a utopian world, a world to counter the many flaws of modern society.

In Swift’s book, the search for this “perfect world” proves a failure. In his photographic reportage, however, the photographer leaves room for interpretation, according to the logic that the world, things, and events, as he represents them, can be analyzed and interpreted from different perspectives, each of which contributes to a better understanding of reality.

This is equivalent to thinking that there is no one way of seeing the world that is the same for everyone.

This new project speaks to social issues, culture, inclusion, legality, love, passion, and freedom—a window onto the 21st century, with its beauty, positivity, and excellence, but also the many contradictions inherent to humanity. This work aims to raise awareness of social issues; perhaps to inspire, motivate, and engage, especially young people, who are increasingly attending the photography exhibitions of this renowned Tuscan artist.

The exhibition features many photographs (in the classroom and during lessons) on the educational system, from the very young, with public preschools and volunteer associations such as the “Born to Read” and “Kamishibai” initiatives, to leading universities such as the IMT School for Advanced Studies in Lucca and the Sant’Anna and Normale Universities of Pisa, and across all levels of education.

Among the impactful social issues, war, racism, immigration, human rights, legality, freedom, violence against women, and road safety could not be missed.

Between Words and Images

During your journey, you will be accompanied by phrases, verses, texts, and quotes (present both in the exhibition and in the printed and purchasable photographic volume) by writers, poets, artists, and scientists whose words have contributed to making the world a better place. This creates a dialogue between photography and writing, two forms of artistic expression that complement each other to narrate, document, and perhaps even move.

FOREWORD

The Search for the Perfect World started in 2023 and was triggered by a fortuitous combination of events, while I was in the south of France with my wife Daniela for a reportage including the lavender bloom.

On that occasion, we set aside a day to visit Nice, the fifth most populated city in France.

Leaving behind its grand Haussmann-inspired boulevards, we immersed ourselves in the Vieux Nice, the old historic quarter, “losing ourselves” in its maze of streets.

Every little alley was a discovery: all similar, yet none the same. Each offered something unique that distinguished it from the others — sometimes in its smells, which could be strong and not always pleasant, sometimes in its looks — but everything was perfectly captured within the frame of the viewfinder on my rangefinder camera and its 35mm lens (whose inseparable bond was forged over the years by my ‘photographic mindset’, my laziness, as well as the laws of mechanics and chemistry known as galvanic corrosion).

In one of those Vieux Nice intersections, where the narrow streets split in two, a surreal scene unfolded before my eyes, throwing me back to the 20th century: a homeless man slept on his side with his head resting on an empty bottle as if it were a pillow, wearing a typical plastic hospital bracelet. By his side lay another, smaller bottle, right next to a drain that — without much effort — made its presence known by its pungent smell.

All this happened in the complete indifference of the people of Nice, the Niçoises (1), busy enjoying their meals, and the shopkeepers, who were repositioning their signs — one of which, in an almost paradoxical twist, offered free chocolate biscuit tastings.

As I documented the scene, my mind went back to a phrase I first read in one of my daughter Eleonora’s university books, coined by the sociologist and philosopher Zygmunt Bauman, originally referring to work ethics in global society. It seemed to fit the moment perfectly:

“Usually, the strength of a bridge is measured on its weakest pillar. The human quality of a society should be measured from the quality of life of its weakest members.”

At that exact moment, I decided to create a reportage entirely different from my recent ones: Vissi d’Arte, a tribute to the greatness of human intellect in the worlds of art, professions, and craftsmanship; The Eye of Time, a nostalgic artistic interpretation of nature forcefully reclaiming spaces once taken by man.

The new project would address society, culture, inclusion, justice, love, passion, freedom — a window onto the 21st century, with its beauty, positivity and excellence, but also its many contradictions, so typical of humanity. A work intended to awaken social conscience; perhaps to inspire, motivate and especially engage with young people, attending my photographic exhibitions in ever growing numbers, partly through school trips.

It was certainly an ambitious plan, as conveying emotions and sensations through photography — in the hope that viewers would be able to appreciate them — was, at least on paper, a complicated task. And I still needed ideas.

I knew from the outset I would have to completely change my photographic approach. It would be a great challenge but also a considerable risk. I would have to compromise between different photographic techniques:

- The classic reportage style, always featuring in my artistic work, would carry the main narrative, especially in visually portraying culture through books, readers and the educational system shaping new generations.

- Street photography (2) would reflect aspects of social life, emotions and human dynamics, revealing a neorealistic view, sometimes dramatic, of the social and economic conditions of the disadvantaged.

- Posed photography, the antithesis of reportage and street photography, would use visual rhetoric to highlight the most controversial and negative aspects of humanity — violence, war, discrimination and justice.

The journey in search of the Perfect World had only just begun.

Over the following months and years, I dedicated a great deal of time to planning, noting down every idea and intuition, initially focusing on the education and training system — ranging from the early years with children in state-run nursery schools and in volunteer associations such as Nati per Leggere and Kamishibai, through every other level of education up to university excellence.

The reason was simple: this journey could not fail to include education — and therefore culture — as the foundation upon which a civil society rests. Had I failed to obtain permission for these shots, there would have been no point continuing the project at all.

By seizing opportunities as they arose, the work grew richer in material content. The project expanded — and I too grew richer, with new experiences, knowledge and a fresh perspective on life: that of others, sometimes of the most vulnerable ones.

The Latin phrase Carpe diem accompanied me throughout the journey. A project like this cannot exist without grasping the moment — that fleeting chance in which one has just a fraction of a second to decide, camera in hand. For example: at one of my exhibitions, I had the pleasure of meeting the Mayor of Altopascio, Sara D’Ambrosio. While we spoke about social inclusion and my new project, she showed me a video of elderly residents from the local care home playing table football with secondary school students — a wonderful intergenerational tournament between people decades apart in age, united not by a video game or some 21st-century gadget, but by a simple game invented more than a century ago. Fascinated, I asked if I could document and perhaps publish it. That event is now part of this journey, along with others introduced by that same mayor, who has a strong commitment to such themes.

When it comes to culture, ‘SAPERE AUDE’ (‘dare to know!’) stands out above all. This is the title of a mural by Piskv, commissioned by the Italian broadcaster RAI in October 2024 as a tribute to the world-renowned science communicator Piero Angela, who passed away in 2022. I photographed the work in February 2025 in the historic centre of Turin, just steps away from the Mole Antonelliana, on the façade of RAI’s historic headquarters. This is a prime example of a simple shot carrying the exact meaning intended by the artist — a piece of visual rhetoric offered directly by the street, amplified and enriched by human presence, revealing its full communicative power. One of the rare cases where street photography itself presents visual rhetoric — now it’s up to you to interpret it.

Among the most socially powerful themes, war could not be overlooked — as an intrusive presence in this delicate historical moment. Two quotes come to mind that inspired some of my shots: the line spoken by Gunnery Sergeant Hartman in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket — veiled by an apparent irony, but deeply revealing the dark side of war:

“It’s a ruthless world, son! You’ve got to hold on until this madness for peace passes!”

And the more rational words of Nobel Prize-winning Chilean poet Pablo Neruda:

“Wars are made by people who kill without knowing each other, for the interests of people who know each other but do not kill one another.”

But not just war — racism, immigration, human rights, justice, freedom, civic responsibility and road safety are also subjects I have sought to bring to public attention in this World Reportage, in which one image stands out in particular: a young mother tending the garden created in memory of her 20-year-old son, on the very site where he died.

Why black and white?

I entrusted my work to the expressive power of black and white because it transforms the ordinary into the extraordinary. Its strength lies in its simplicity and emotional impact. Emotions are heightened; it forces us to observe the whole scene attentively, uncovering even the smallest details — those revealing the soul of the image.

Here I quote the English photographer Bill Brandt, whose words best represent my choice of black and white for this specific reportage:

“In colour photography there is the whole world;

in black and white there is only the world you choose to see.”

I hope that in this journey, made of photographs that reveal our time, you can find the answer to what happens outside that magical rectangle that we photographers call a frame. But the “answer” of what will remain after each shot can only be found within yourself, because in every photograph “you can see what you choose to see.”

Enjoy the view

Dantès (Dante Luci)